FLUID LIQUIDATION MECHANISM: A CLOSER LOOK AT TICKS AND BRANCH LIQUIDATION DESIGN

Fluid Vault and its truly “fluid” liquidation mechanism, optimized for smooth execution, high efficiency, and strong protection for both users and the protocol.

INTRO

In most lending protocols, liquidation feels like a penalty, collateral is sold off at a discount, and liquidators capture the spread.

Fluid, a protocol launched by Instadapp, seems to approach this problem differently by introducing a new era of liquidation mechanism. This article will deep dive in this liquidation machine, provide a closer look at the concepts of ticks and branches, and the way liquidators operate inside this framework.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Fluid Vault became a significant trend in borrowing protocol by allowing users to borrow max (up to 95% as LTV) and pay min in case of liquidation (down to 0.1%). Fluid makes it possible by enabling a smart liquidation mechanism, including:

Partial liquidation before fully liquidation (Section 1): When a position reaches the liquidation threshold, Fluid only sells a part of the collateral to cover a part of the debt which makes this position safe again. Full liquidation is only triggered when max liquidation threshold is reached.

Ticks and branches liquidations (Section 2): To reduce liquidation gas fee in maximum, Fluid enables positions in a tick to be liquidated in only one transaction. A branch includes liquidated ticks in a specific period of time. When the liquidation threshold of a tick touches the base branch’s one, it will be merged with base branch and being liquidated in one transaction, gas fee continues to be reduced.

Liquidator bots and traders as liquidator (Section 3): Liquidation bots is the main liquidation method of Fluid, making sure that Fluid can liquidate unhealthy positions on time. Liquidations can also work like a swap, this means any trader of any size can liquidate any amount of debt.

PROBLEMS: THE ROLE OF LIQUIDATION IN DEFI LENDING AND CHALLENGES

1/ The role of liquidation in DeFi lending

Liquidation is a critical safety mechanism in DeFi lending protocols. When a borrower’s collateral value drops too low compared to their debt, the protocol automatically sells their collateral to repay the loan. This prevents the protocol from losing money and protects other users’ funds.

Liquidation plays an important role in maintaining lending’s system stability and preventing bad debts. Without it, protocols would face massive losses when collateral prices crash, potentially leading to collapse where depositors can’t pay back their debt. Liquidators act as market stabilizers, quickly removing risky positions before they become bad debt.

2/ Key challenge: Loan-to-Value and Liquidation Trade-off

DeFi lending protocols cannot simultaneously offer high LTV ratios and gentle liquidation mechanisms at a time. High LTV (80-90%) protocols must implement harsh liquidation rules - instant triggers, large penalties, and complete position closure - because there is minimal safety margin when collateral prices drop. Whereas, low LTV (50-70%) protocols can afford softer liquidations with lower liquidation fee and lower loss for borrowers, but this conservative approach makes them less competitive than protocols offering higher capital efficiency.

HIGH-LEVEL DESIGN: LIQUIDATION MECHANISM IN FLUID’S VAULT PROTOCOL

1/ Partial Liquidation and Full Liquidation

In Fluid, a borrower’s position can be liquidated either partially or fully. When a position reaches the liquidation threshold, partial liquidation will be triggered to sell a part of the collateral to cover a part of the debt which makes this position safe again. If position goes above the liquidation threshold and reaches the max liquidation limit, full liquidation closes the entire position. This mechanism protects the system from bad debt.

We will discuss the details in Section 1.

2/ Ticks and branches liquidation

Branches in Fluid Vault manage sequential liquidations within specific tick ranges where collateral becomes under-collateralized. Each branch tracks ticks eligible for liquidation, allowing the protocol to reduce bad debt and restore safe collateral levels without touching individual positions. As liquidation progresses, branches may merge at their minimal tick, streamlining the process efficiently. This structure ensures controlled, gas-efficient liquidations while maintaining protocol stability.

We will deep dive into this mechanism in Section 2.

3/ Liquidator bots and liquidator traders

Liquidations are executed by liquidators, which can be automated bots or human traders. Bots act instantly to capture opportunities. In addition, liquidations can also work like a swap but with better rates, which means traders can liquidate an amount of a debt through trading transactions.

More explanation will follow in Section 3.

SECTION 1: PARTIAL LIQUIDATION AND FULL LIQUIDATION

In Fluid, liquidation depends on how high the Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratio gets when collateral prices fall. There are two important thresholds: Liquidation Threshold (trigger partial liquidation) and Liquidation Max Threshold (trigger full liquidation).

If your LTV goes above this level, the system will liquidate part of your collateral. The goal is to sell just enough collateral so that your position goes back below the safe zone.

This is called partial liquidation.

But a position can go above the liquidation threshold without being liquidated immediately. In Fluid, positions are not liquidated instantly when they pass the threshold. Instead, liquidations are executed gradually by ticks (We will discuss “tick” in the next section). This means a tick can stay above the liquidation threshold for several blocks if no trader or bot chooses to act yet. If no one acts and the LTV keeps rising, it will eventually hit the max liquidation limit, where the protocol liquidates everything at once.

This is called full liquidation.

For example:

Collateral factor (LTV) = 87% → max borrow = $34,800 USDC.

Liquidation Threshold = 92%

Liquidation Max Limit (above which positions will be fully liquidated) = 95%

You deposit: 10 ETH = $40,000 collateral (ETH = $4000)

Your borrowed amount = $34,000 USDC.

Starting LTV = 34,000 ÷ 40,000 = 85% (you’re safe, below 87%).

Scenario 1 - No liquidation: ETH drops to $3,800

Your collateral = 10 × 3,800 = $38,000.

Your current LTV = 34,000 ÷ 38,000 ≈ 89.5%.

Still below liquidation threshold (92%), no liquidation required.

Scenario 2 - Partial liquidation: ETH drops to $3,600

Your collateral = 10 × 3,600 = $36,000.

Your current LTV = 34,000 ÷ 36,000 ≈ 94.4%.

Now above 92%, so liquidation is triggered.

But since it’s still below liquidation max limit (95%), only partial liquidation happens. The protocol sells just enough ETH to bring your LTV back under 92%.

Let X (USD) be the value of the collateral sold. Assuming a 0% liquidation fee, X also corresponds to the portion of the debt that the liquidator repays on your behalf.

Therefore, X satisfies the condition:

Therefore, instead of liquidating the whole position, the system only liquidates an enough part to bring the LTV back to a safe level.

Scenario 3 - Full liquidation: ETH drops to $3,400

At the previous price level, your collateral had already touched the liquidation threshold, but before it’s liquidated, the collateral value continues to drop to $3,400.

Your collateral = 10 × 3,400 = $34,000.

Your LTV = 34,000 ÷ 34,000 = 100%.

Now above liquidation max (95%), so your entire position is fully liquidated.

SECTION 2: TICKS AND BRANCHES LIQUIDATION

1/ A tick of positions

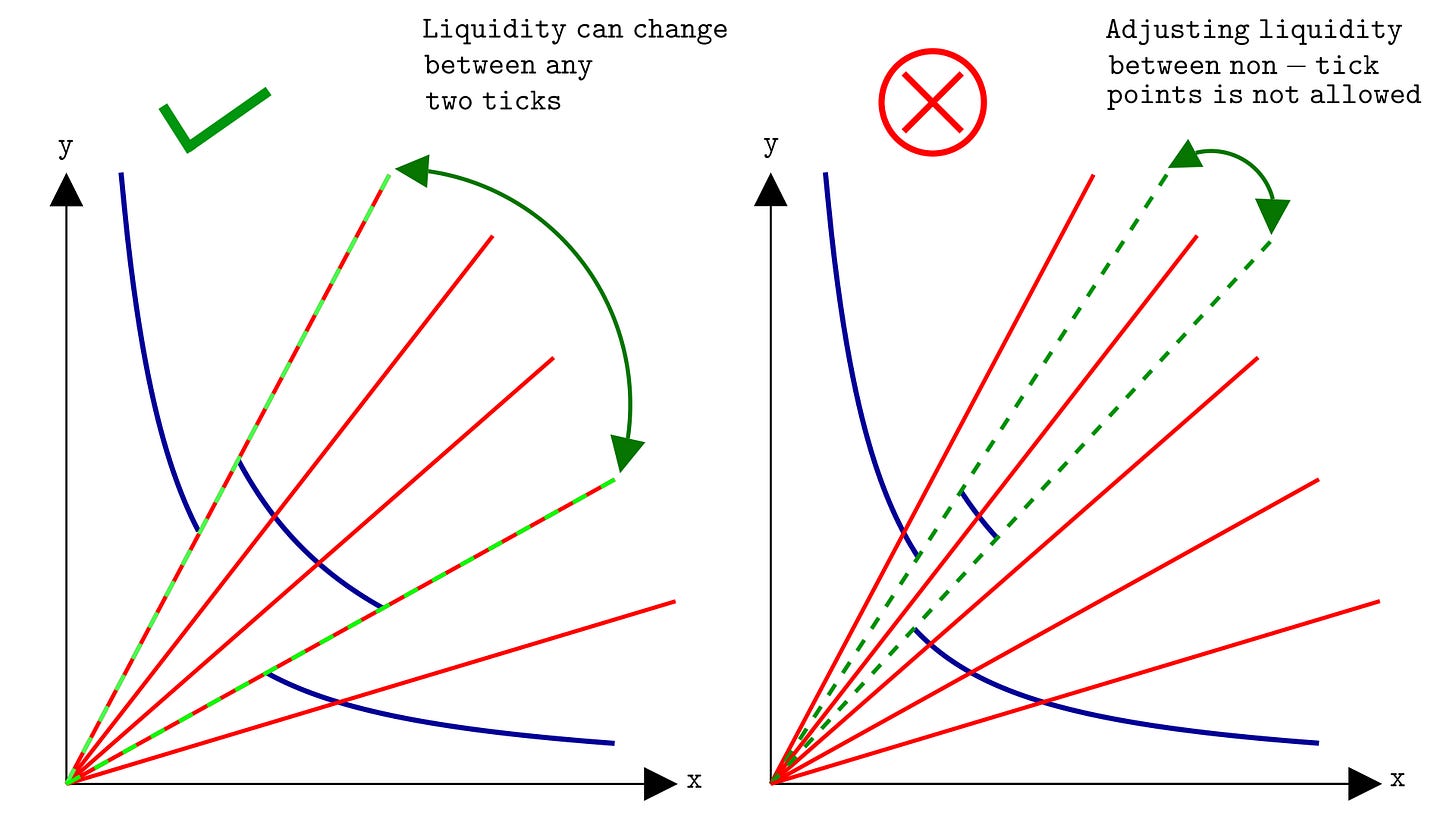

Uniswap V3 ticks idea

The liquidation mechanism of the Vault protocol is loosely inspired from the Uniswap V3 design. It achieves that by allocating the liquidity such that all users in the range get liquidated simultaneously instead of one-by-one leading to a significant decrease in gas cost.

Firstly, let’s take a very quick look at how Uniswap V3 creates “price ticks”:

In Uniswap V3, liquidity (the pool of tokens available for trading) is not spread evenly everywhere, it can be concentrated around certain price ranges.

But here’s the problem: if liquidity could be placed at any random price point, the system would become super complicated and expensive to run. Every tiny move in price would force the protocol to check whether liquidity changed at that exact point.

To make things simpler and cheaper, Uniswap V3 only allows liquidity to change at certain fixed price levels. These fixed price levels are called ticks.

You can think of ticks as “markers” along the price line, like rungs on a ladder. Instead of checking every possible price, the protocol only needs to look at these tick points. The price curve is basically sliced up by these ticks.

Source: RareSkills - Introducing ticks in Uniswap V3

Similarly, in Fluid Vault protocol:

When a position becomes unhealthy, instead of being liquidated one by one, the liquidator has to identify each bad position separately (which makes the process slow and complicated), the system allows all bad positions to be liquidated together in a single action.

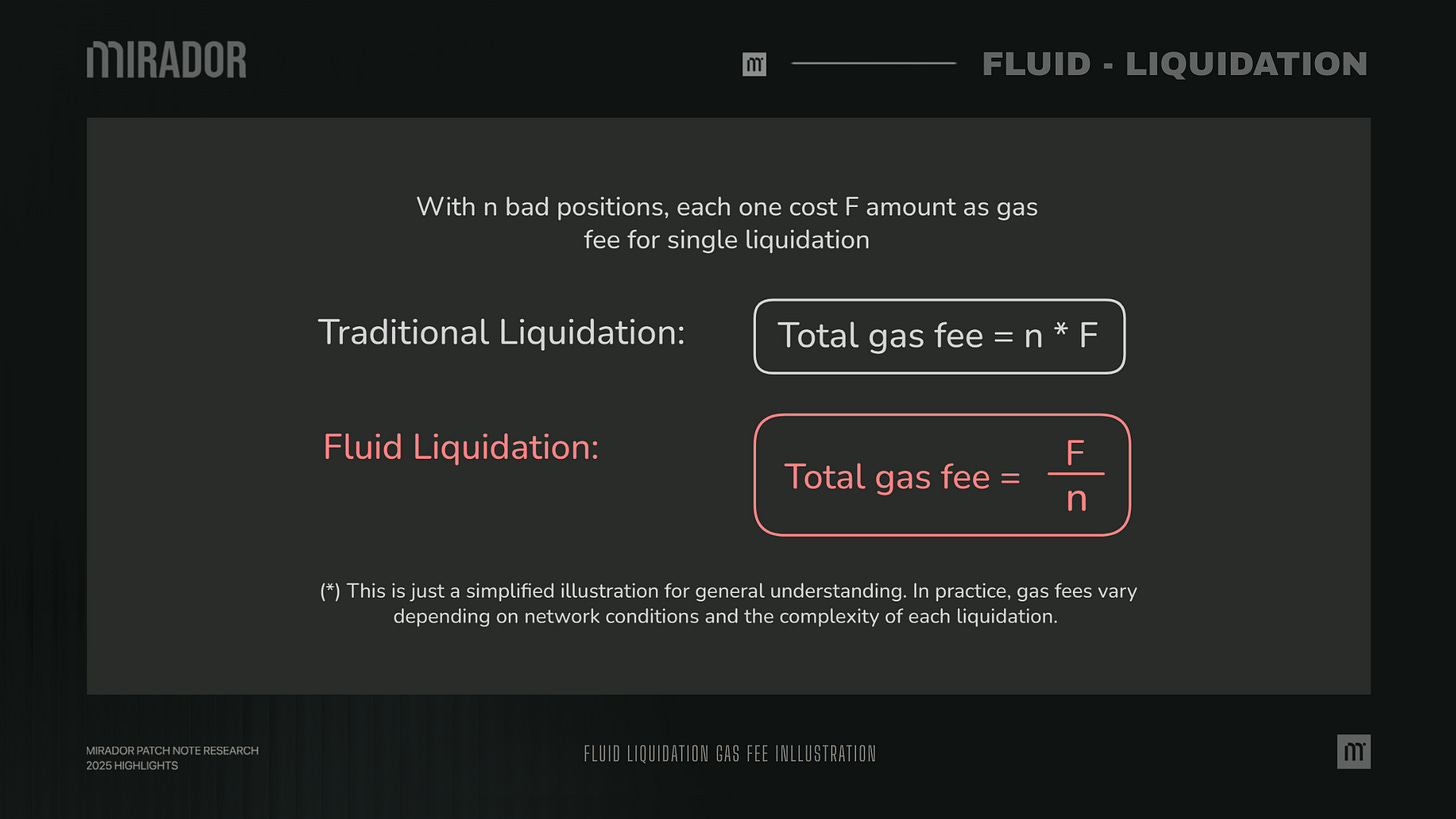

This liquidation machine in Fluid is 100x better in comparison to traditional borrowing protocol. Sounds unreal, so let’s make a simple calculation:

In most lending systems, when a borrower’s position turns bad, it has to be liquidated separately. Each liquidation is its own transaction, so every borrower has to pay for their own gas fee, sometimes even at the maximum gas cost. If there are 100 bad positions, that means 100 separate transaction fees.

The Vault protocol changes this. Instead of liquidating one by one, all bad positions can be liquidated together in a single transaction. That means the transaction fee (even if it’s the maximum possible) is paid only once and then shared across all liquidated borrowers.

Says there are n bad positions waiting for liquidation, each transaction in Ethereum blockchain cost F amount as gas fee, we have a simple look:

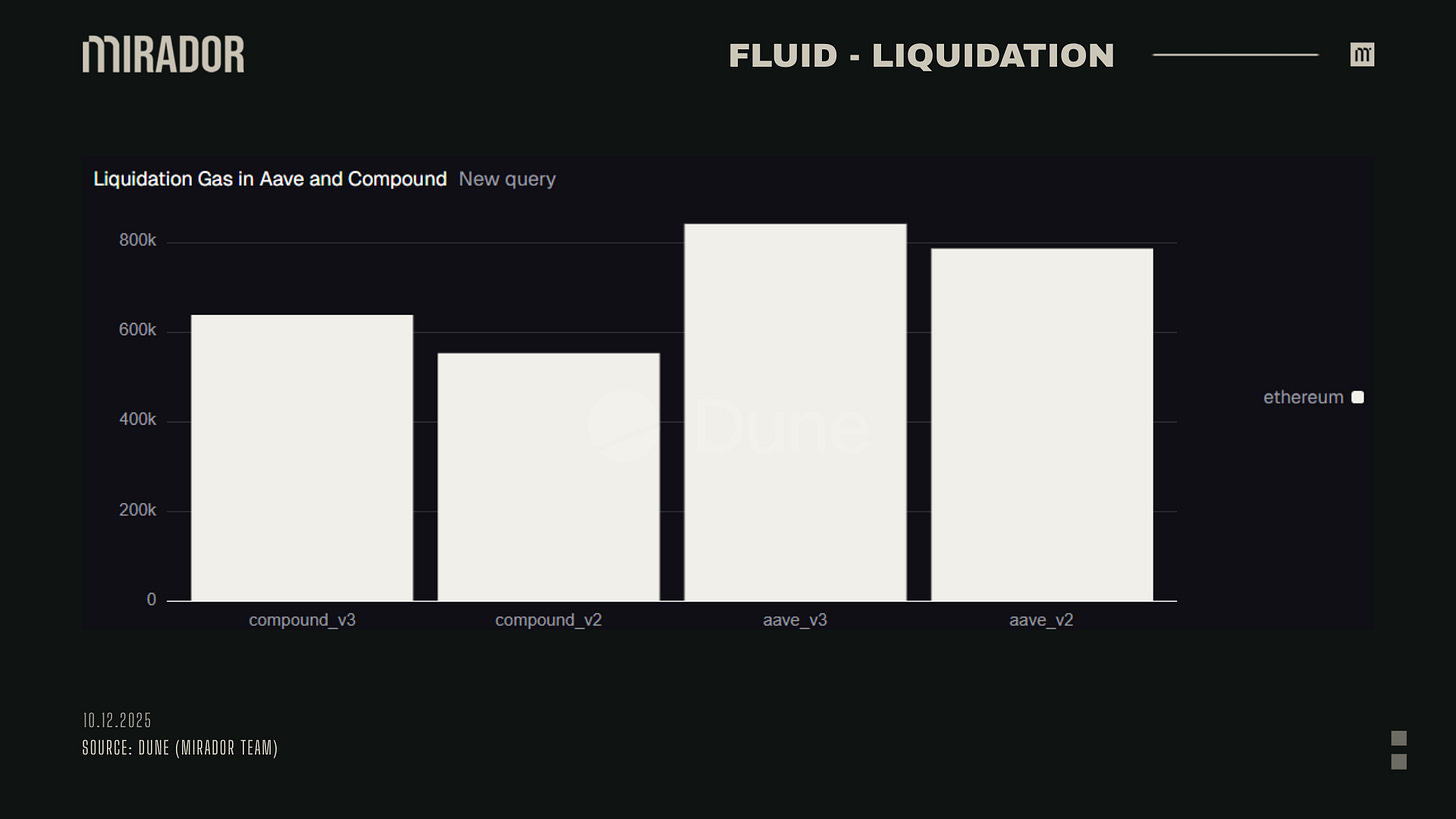

Due to Fluid introduction, the gas cost of liquidation is around ~150k. In comparison a Uniswap V3 swap is ~120k and liquidations in lending protocols range from 300k to 1M for a single position.

The values 150k, 120k, 300k–1M represent gas units, which measure how much computation a blockchain transaction requires. Lower gas usage means lower costs and a more efficient protocol.

Fluid is designed to be highly gas-efficient.

While many lending protocols require 500k to nearly 1M gas for a liquidation.

Liquidations on Fluid are simpler and require less gas. Due to Fluid introduction, a typical liquidation costs around 120k–130k gas. When using the more advanced oracle logic currently in place, this cost increases to about 200k gas.

Source: @DeFi_Made_Here

This indicates that Fluid’s liquidation process is highly optimized, which reduces liquidation costs, encouraging liquidators to process even smaller positions. This helps maintain system health and reduces the chance of bad debt.

Liquidation by ticks

When a user creates a position, the protocol assigns it to a specific tick based on the user’s debt-to-collateral ratio, with the tick calculated as:

Debt: The amount the user has borrowed.

Collateral: The value of assets the user has locked.

Ratio: A measure of leverage (how much debt compared to collateral).

Tick: A discrete step into which the ratio is mapped.

This tick represents the user’s debt-to-collateral ratio, which determines how close their position is to liquidation.

The tick number therefore determines the liquidation priority:

Lower tick = lower ratio = safer position (more collateralized)

Higher tick = higher ratio = riskier position (closer to liquidation).

For example:

Let’s consider a position with Loan-to-Value (LTV) approximately 87%

Using the tick formula, this position is assigned to tick -92

Now, suppose three users’ positions:

Alice: 10 ETH collateral, 8.7k USDC debt (LTV = 87%)

Bob: 5 ETH collateral, 4.35k USDC debt (LTV = 87%)

Carol: 20 ETH collateral, 17.4k USDC debt (LTV = 87%)

Since they are all in the same LTV range, their positions are grouped into Tick -92.

The number 1.0015 is the step size between ticks. Each tick is 0.15% riskier than the previous one. The protocol groups positions into very small intervals, so each tick represents a narrow level of debt-to-collateral ratio. Even a small movement in debt or collateral can push you into the next tick.

The function getTickAtRatio() in Fluid’s smart contracts is used to map a debt/collateral ratio into a tick value.

Debt/Collateral ratio and tick are connecting with formula: ratio = (1.0015)tick (Ratios are stored in Q96 fixed-point format (multiplied by 296) for precision)

The tick is always an integer, and a tick can be either a positive number or negative number. The tick is always floored (rounded down).

2/ A branch of ticks

Fluid is a system that manages user positions (like loans or collateral) based on price movements. It uses ticks to track price levels, and branches to organize liquidation events.

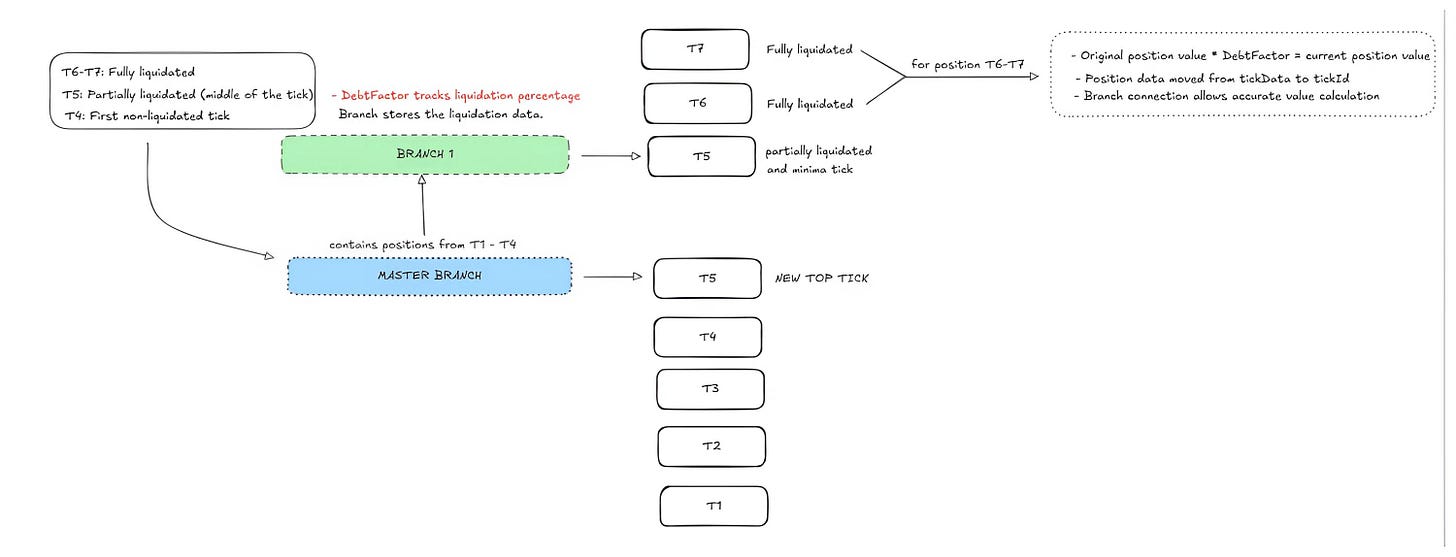

In Fluid, a branch represents a collection of ticks that have crossed the safe debt-to-collateral threshold. This means branches will not be created at every tick. Users’ positions are not tied to any specific branch when creating a position. All active positions are in “Master branch”.

The Master Branch is simply a name used to represent the set of all ticks that are currently considered safe. It serves as a reference point for the system.

When you create a position, you do not need to explicitly declare that you are “in the Master Branch.” The system implicitly treats every position as part of the Master Branch as long as it has not been separated out.

In other words, any position that has not triggered a branching event is automatically regarded as belonging to the Master Branch.

Branch is created when the current top tick (position at highest ratio) in master branch is in liquidated state. All users whose positions above the current top tick will have their liquidation in this same branch.

Master branch of regular active ticks

This section is based on an interesting breakdown by @DeFi_Made_Here in the post below. The key points will be unpacked and analyzed in detail right after this.

https://x.com/DeFi_Made_Here/status/1943383547517325692?s=20

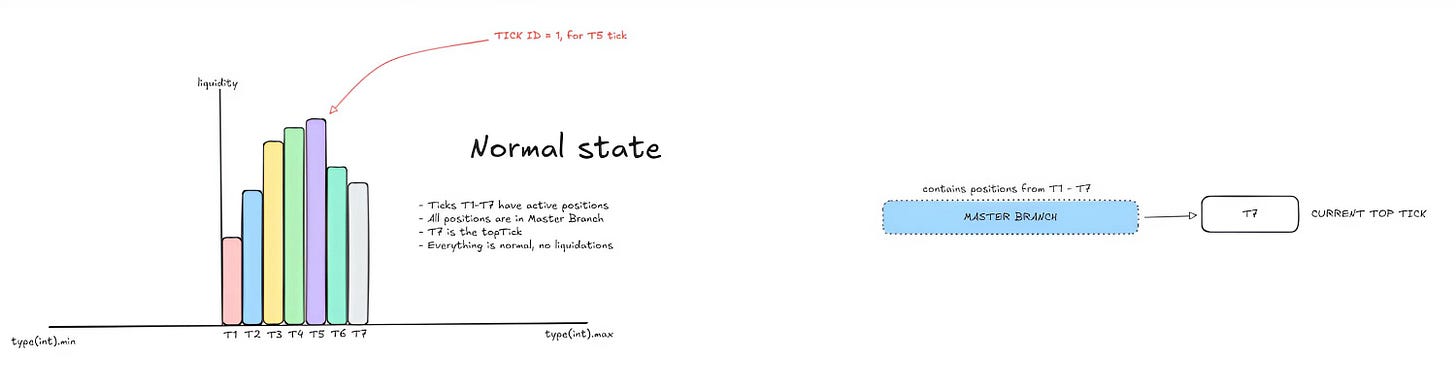

Says there are 7 active ticks T1 to T7. This diagram shows the normal state of the system.

Each bar (T1–T7) represents a tick, which is a range of positions grouped by their debt-to-collateral ratio.

The height of each bar reflects the total liquidity (collateral) in that tick.

All positions are currently inside the Master Branch (the main branch that tracks every active position).

T7 is the topTick, meaning it’s the riskiest tick but still below the liquidation threshold.

Since no tick has crossed the liquidation line, everything is stable and no liquidations are triggered.

Source: @DeFi_Made_Here

Then, let’s see what happens in the Post Liquidation state of a branch in Fluid Protocol:

Source: @DeFi_Made_Here

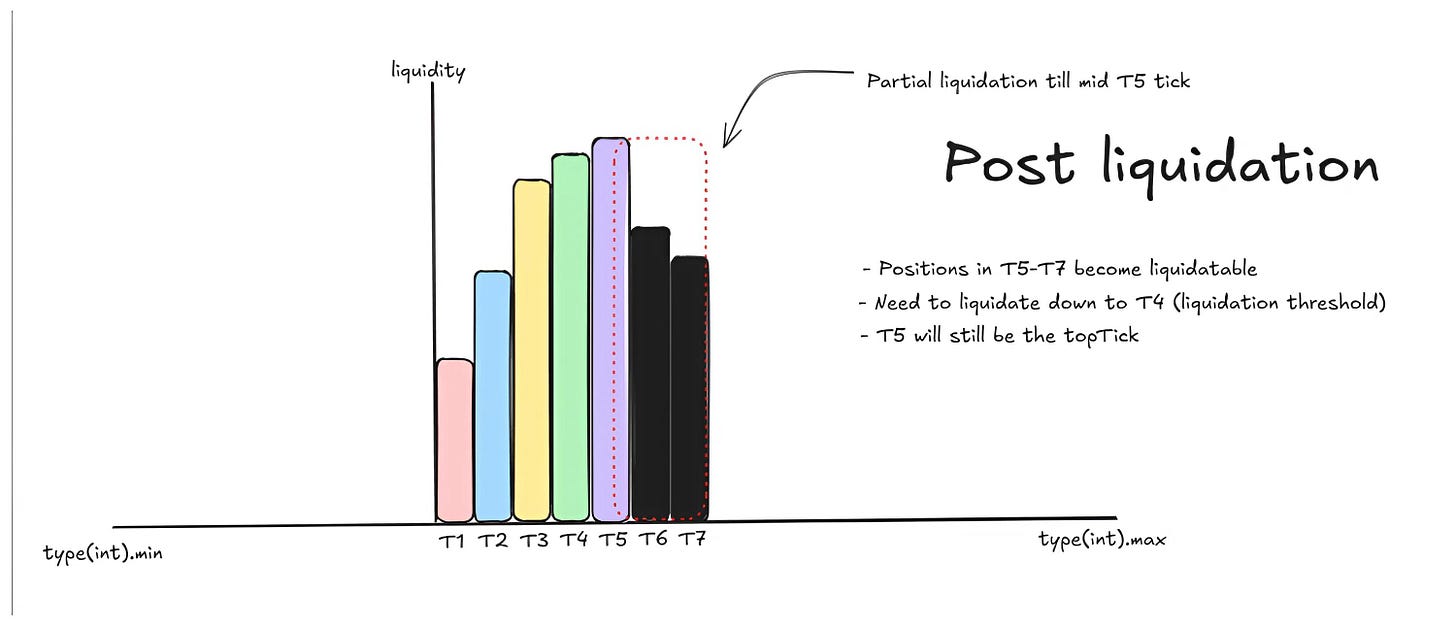

Once the collateral value drops, the system requires liquidation down to the liquidation threshold, which is at T4.

That means positions in T5, T6, T7 are above the safe limit and must be liquidated. The liquidation engine’s goal is to bring positions back below the safe LTV threshold.

T7 and T6 are above the maximum liquidation threshold, which means they are fully liquidated (their entire positions are closed).

T5 is just slightly above the liquidation threshold, still under maximum liquidation threshold, this means it is only partially liquidated. Its liquidity is reduced just enough so that the system’s aggregate ratio returns back to threshold (T4).

Source: @DeFi_Made_Here

So after liquidation:

T5 remains the topTick, but with reduced size (smaller liquidity).

T6 and T7 no longer exist, since they were fully cleared.

A new Branch ID 1 is now created to store liquidation data.

The Master Branch continues safely with positions T1–T4, while T5 (cut partially but kept) becomes the new Top Tick after liquidation.

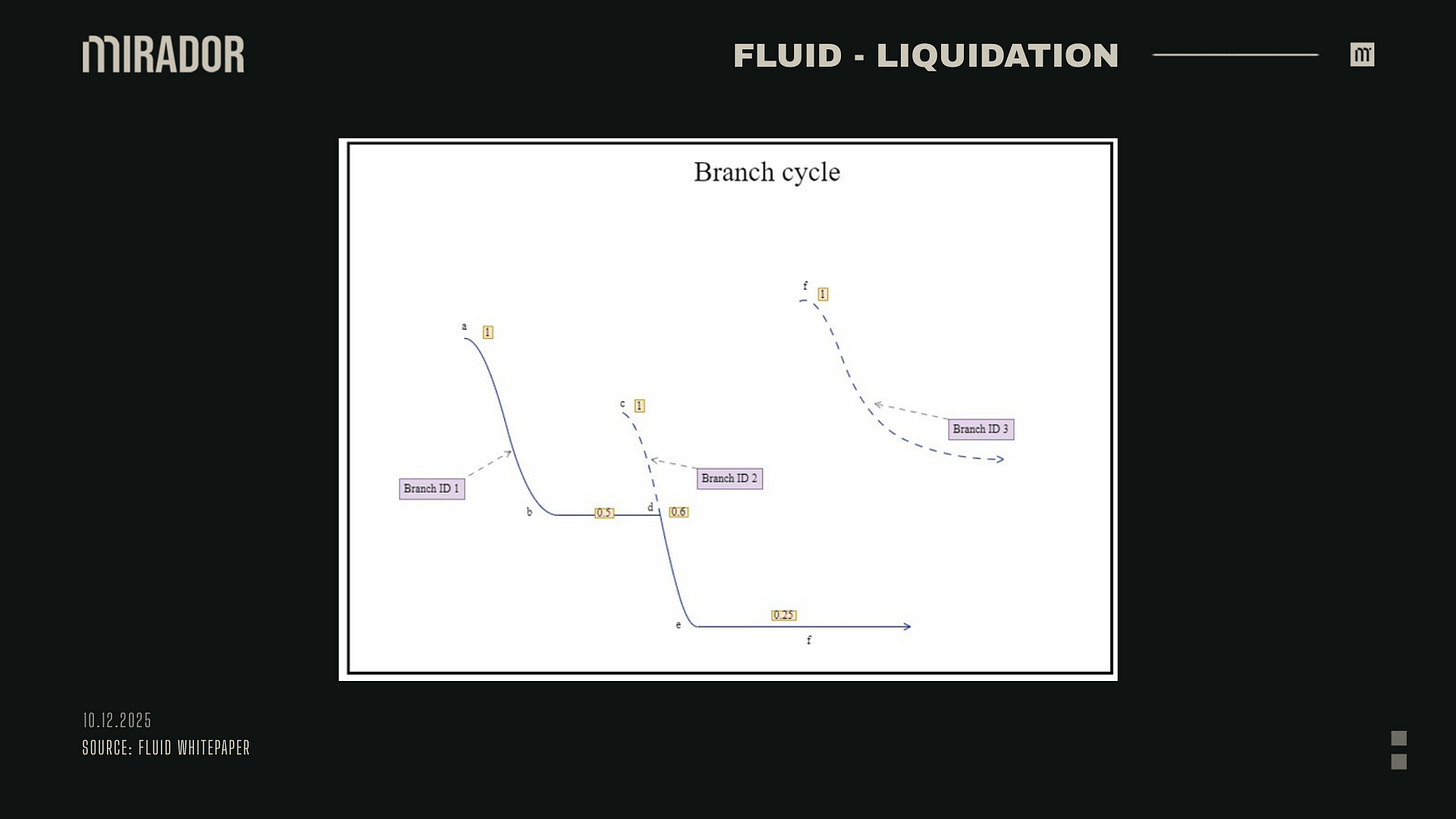

New Branch creating and Branches merging

As we have mentioned, Branch is created when the current top tick (position at highest ratio) in master branch is in liquidated state

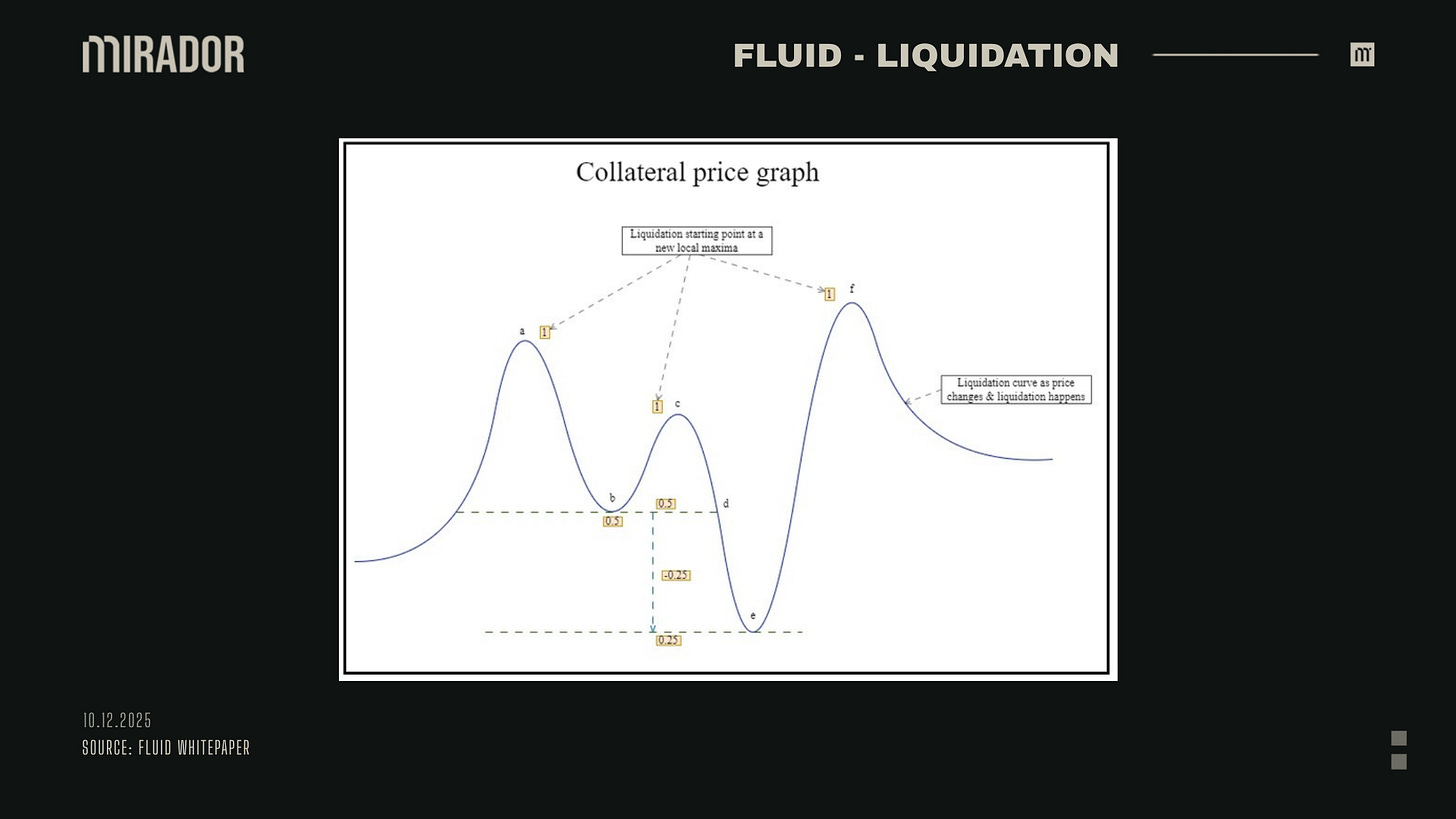

Firstly, let’s take a deep look at Collateral Price Graph:

Source: Fluid Whitepaper

Local maxima (a,c,f) is high points in the price cycle of a collateral asset (like ETH). It’s where the price peaks before starting to fall again.

In Fluid, these points are important because they represent potential entry points for new users. Says, when the price is high at (a) point, users may open positions at that tick. A branch doesn’t actually begin until the price drops and users at that tick are affected

For example:

a: $4,000 → b: $3,500 → c: $3,800 → d: $3,500 → e: $3,000 → f: $4,500

Point a is a local maxima → users enter, the top tick in master branch is (-90)

Price drops to b → users at top tick (-90) are partial liquidated

→ Branch 1 is created, the liquidation process occurs until this tick reach the minimum tick at (b) point, says it’s tick (-94)

Point c is another local maxima → users enter, the top tick in master branch is (-92)

Price drops from (c) to (e) → users at top tick (-92) are partial liquidated

→ Branch 2 is created, the liquidation process occurs until this tick reach the minimum tick at (e) point, says it’s tick (-95)

→ But when branch 2 reach (d) point - tick (-94) - the minimum tick of branch 1, Branch 2 merges into Branch 1, which means there will be more liquidation happening in Branch 1

→ Users in tick (-94) of both Branch 1 and Branch 2 now are liquidated together to reach the minimum tick at (e) point, says it’s tick (-97)

Source: Fluid Whitepaper

As a result, when smaller branches reach an existing branch or the master branch, they merge and are processed together, the debt and collateral for all users in the branch can be calculated in a consistent way. This reduces the number of on-chain operations, saving gas and operational overhead.

Debt Factor - the proportion of debt that remains after liquidation.

For example, in the graph, at point (b): debt factor = 0.5, which means if you opened your position at (a), after liquidation at (b) you only retain 50% of the initial debt.

When the collateral price reaches a new local maximum (c), a new branch starts and the debt factor is set back to 1. And one more time, if price decreases to (d) point, you only retain 50% of previous debt and if it continues to decrease to (e) point, you lose 25% and only retain 25%.

SECTION 3: LIQUIDATOR BOTS AND TRADERS AS LIQUIDATOR

Liquidator Bots

Liquidation bots is the main liquidation method of Fluid, making sure that Fluid can liquidate unhealthy positions on time, because liquidator, in this case, do not spot the liquidation opportunity manually, but run a script (a bot) and deploy it on a server, so that it runs 24/7. “Less than 1 second” is how long does a bot usually take to liquidate a bad position, helping protect the protocol from bad debt risk.

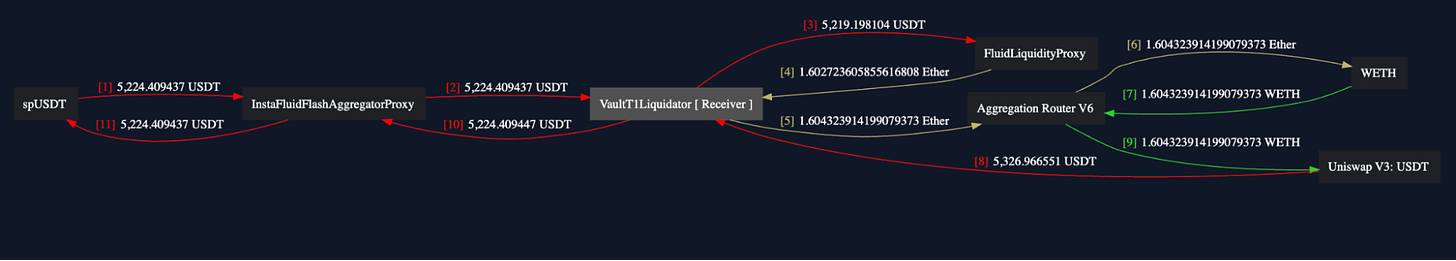

Let’s take a look at a real liquidation process in Fluid Vault T1 (regular vault):

To liquidate a position on Fluid, the liquidator has to repay the debt of the under-collateralized user. In this case, it requires about 5.2k USDT to repay the debt. The liquidator bot usually doesn’t hold that much capital, so it uses a flash loan: borrow a large amount instantly, use it within one transaction, then repay it immediately.

[1] Liquidator bot called InstaFluidFlashAggregatorProxy to temporarily borrow 5,224.409437 USDT from the spUSDT pool.

[2] These USDT was sent to VaultT1Liquidator (Liquidator Bot wallet)

[3] The liquidator used it to repay the debt of the liquidated position. Tokens were transferred to FluidLiquidityProxy (Liquidity Layer) to pay back the bad debt.

[4] The vault released the collateral and bonus back to the liquidator (here is about 1.6 ETH)

[5] Liquidator bot swapped the 1.6 ETH for USDT (to lock the profit) through AggregationRouterV6 (1inch DEX aggregator).

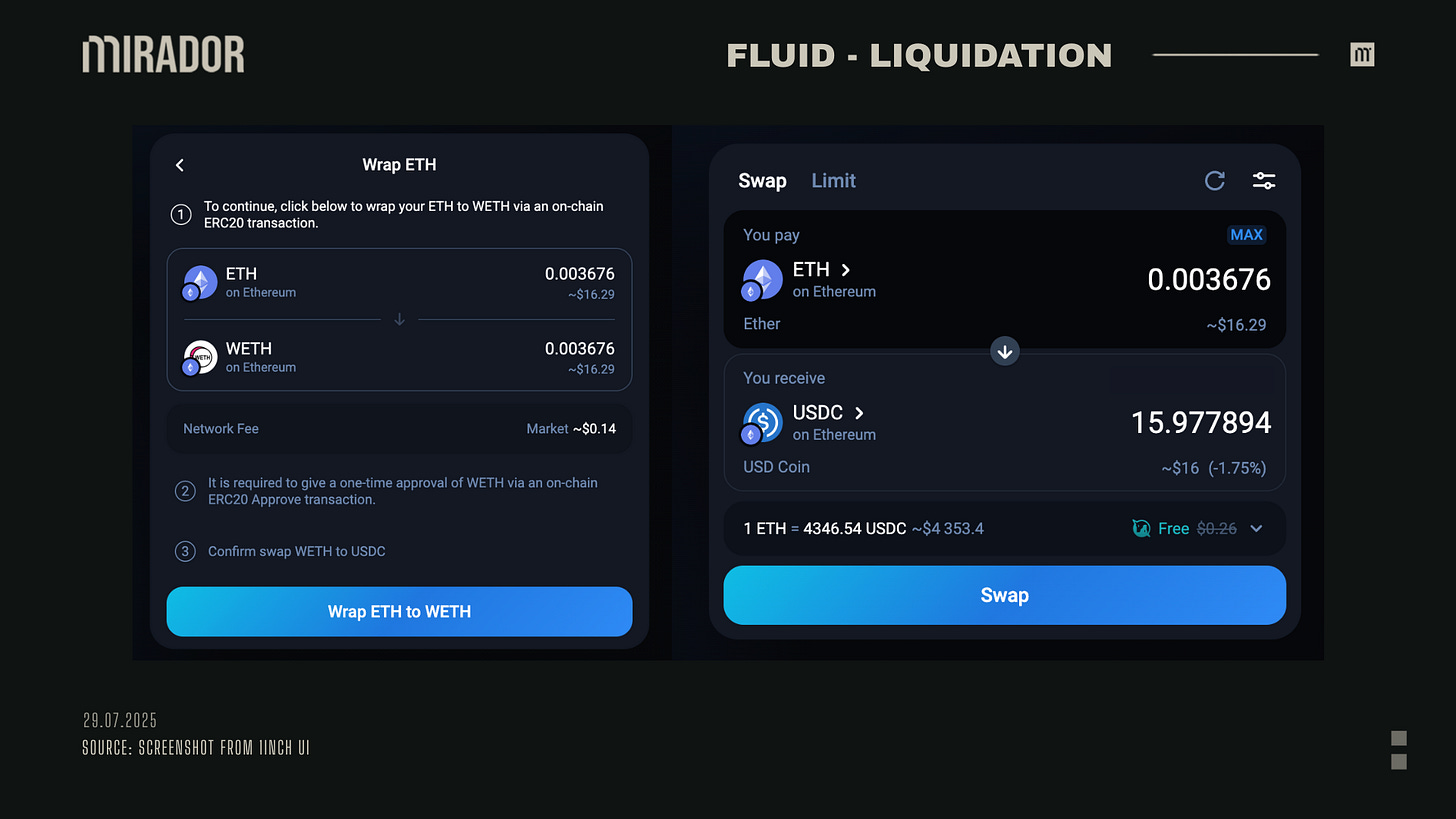

[6] 1inch firstly swapped ETH to WETH via an on-chain ERC20 transaction. This is an essential step with every interaction with 1inch aggregator. Here is an example:

[7] to [9] 1inch routed this WETH-USDT swap to Uniswap V3. Liquidator bot finally received more than 5,326 USDT (this amount is bigger than the debt it had to payback for flashloan, which is about 5,224 USDT)

[10] to [11] Liquidator bot repays 5,224 USDT flash loan to spUSDT

As a result, the excess of about 100 USDT is the profit kept by the liquidator.

Traders as liquidators

One of the most interesting and outstanding liquidation features in Fluid Vault protocol is liquidations work like a swap but with better rates. It is possible by the way DEX aggregators will route traders to liquidation when they make swap transactions, creating a win-win solution: bad positions can be liquidated with lower rate of loss and traders can have a greater rate too.

A DEX aggregator is a tool that searches across many decentralized exchanges (DEXs) to find the best price for a trade. Instead of swapping on just one DEX, it splits or routes your order through multiple DEXs to reduce slippage and get you the most tokens for your trade (we will discuss about this more in the following section)

For DEX aggregators, the integration is as simple as adding any other AMM, allowing traders to get better prices. This means any trader of any size can liquidate any amount of debt. There’s no requirement to liquidate the entire bad debt at once. This allows even the smallest trade to liquidate bad debt on time and traders get the best price under no circumstances.

CONCLUSION

Fluid redesigns the liquidation mechanism to maximize system safety while minimizing user costs. By combining partial liquidation, a ticks–branches structure, and a flexible liquidator model, Fluid can process multiple positions in a single transaction, sharply reducing gas and avoiding unnecessary losses for borrowers. This approach sets a new standard for lending protocols: keeping high LTVs while still maintaining strong risk control. As competition in on-chain capital markets intensifies, Fluid’s liquidation design becomes an important case study in how to improve capital efficiency without compromising system security.

DISCLAIMER

In this article, we focus on exploring the liquidation mechanism of Fluid Vault, a protocol built at the protocol layer of Fluid Finance. This mechanism is relatively unique compared to those of other lending protocols, as it is designed around two novel concepts: ticks (position buckets) and branches (groups of ticks). Our goal is to provide readers with a deeper understanding of how this system works and how it affects users’ capital efficiency.

Throughout the article, we do not avoid discussing mathematical concepts or visual charts that may appear complex. However, all of these elements are simplified and thoroughly explained to ensure the content remains accessible and easy to follow.